"What is the object of knowledge?" asks young Grasshopper. "There is no object of knowledge," replies the old Shaman, "To know is to be able to operate adequately in an individual or cooperative situation." "So which is more important, to know or to do?" asks young Grasshopper. "All doing is knowing, and all knowing is doing," replies the Sage, and then continues, "Knowing is an effective action, that is, knowledge operate effectively in the domain of existence of all living creatures." [paraphrased from Maturana & Varela].

One of the most popular epistemology models (except in the behavioral sciences) is Sir Karl Popper's writtings on the Three Worlds of Knowledge. The knowledge/learning/management professions seem to prefer and stay within the realm of Michael Polanyi's concept of personal and tacit knowledge. However, Polanyi's epistemology is narrower and has a limited basis for understanding knowledge as compared to Popper’s work, which provides a broader epistemological foundation.

Click to enlarge

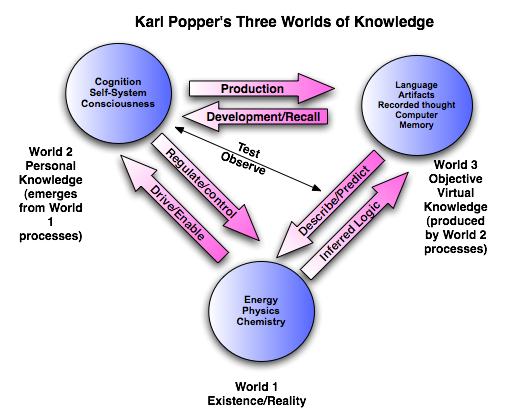

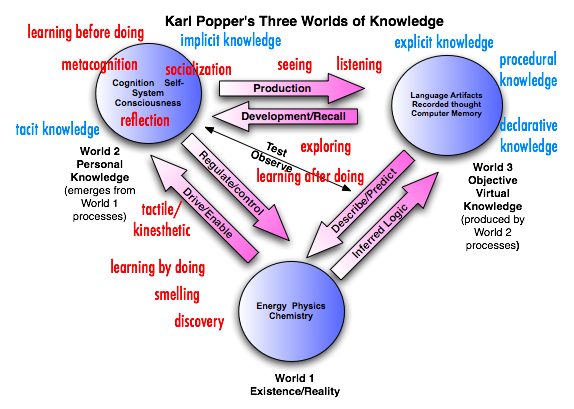

Karl Popper theorizes that there are three worlds of knowledge:

- World 1 is the physical universe. It consists of the actual truth and reality that we try to represent, such as energy, physics, and chemistry. We may exist in this world, however, we do not always perceive it and then represent it correctly.

- World 2 is the world of our subjective personal perceptions, experiences, and cognition. It is what we think about the world as we try to map, represent, and anticipate or hypotheses in order to maintain our existence in an every changing place. Personal knowledge and memory form this world, which are based on self-regulation, cognition, consciousness, dispositions, and processes. Note that Polanyi's theory of knowledge is based entirely within this world.

- World 3 is the sum total of the objective abstract products of the human mind. It consists of such artifacts as books, tools, theories, models, libraries, computers, and networks. It is quite a diverse mixture that ranges from a claw-hammer to Maslow’s hierarchy to Godel's proof of the incompleteness of arithmetic. While knowledge may be created and produced by World 2 activities, its artifacts are stored in this world. Popper also includes genetic heredity (if you think about it, genes are really nothing more than a biological artifact of instructions).

And of course, there are various relationships between these three worlds:

- World 1 drives and enables world 2 to exist, while world 2 tries to control and regulate world 1.

- World 2 produces world 3, while world 3 helps in the recall and the training/education/development/learning of world 2.

- World 3 describes and predicts world 1, while world 1 is the inferred logic of world 3.

In addition, since world 2 is composed of people, we can use our senses to cut across boundaries and observe and test the exchanges and relationships of worlds 1 and 2.

Thus, knowledge surrounds us (world 1), becomes a part of us (world 2), and is then stored in historical contents and contexts by us (world 3 artifacts).

In this framework are two different senses of knowledge or thought:

- Knowledge in the subjective sense, consisting of a state of mind with a disposition to behave or to react [cognition].

- knowledge in an objective sense, consisting of the expression of problems, theories, and arguments.

While the first is personal, the second is totally independent of anybody's claim to know -- it is knowledge without a knowing subject.

A T ~ T H E ~ F I S H H O U S E S

by Elizabeth Bishop

It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

Thus, knowledge goes far beyond the knowing/doing dichotomy. . . it is drawn, derived, flowing, historical, and forever.

Click to enlarge

A few examples:

S E N S E S

Give a baby an object and one of the first things they normally do is "mouth" it. While this is sometimes done to massage their gums due to cutting teeth, it is also performed to learn about the object. Babies are just as curious about their surroundings as we are. The mouth and tongue are filled with sesitive nerve endings that allow them to not only feel, but also taste objects. Thus our first learnings are done by hearing, seeing, tasting, and feeling not only our hands, but also with our mouths.

Our senses are basically multifaceted in that we learn about world 1 through our senses and then create world 3 artifacts within world 2, which in turn helps others in their quest of learning by using their senses to understand world 3 artifacts in order to live more productively within world 1 (whew -- what a breath full). In addition, we test the interrelations of worlds 1 and 2 with our senses.

M I R R O R ~ N E U R O N S

Our brain contains a special class of cells, called mirror neurons, that fire not only when we see or hear an action, but also when we carry out the same action on our own. Our survival depends on understanding the actions, intentions and emotions of others, and by using these special mirror neurons, we are able to grasp the minds of others through direct simulation, rather than through conceptual reasoning. Thus knowing and doing become one -- at least in our minds!

Mirror neurons reveal how we partly learn; why people respond to certain types of sports, dance, music and art; why watching media violence may be harmful; and why we may like voyeurism or pornography. We are simply hardwired for imitation.

For more information, see the video and audio clips.

L I S T E N I N G

Listening is instinctual -- we can automatically home in on specific conversations at large gatherings. And as Chomsky theorized, it is hard-wired within us for children do not really learn to understand the spoken word, they just do it. In addition, listening frees our hands and eyes so we can take notes, draw mind maps, and do other useful things with our hands (create 3rd world artifacts).

People normally enjoy listening to others. . . it is part of our social nature. Listening to someone directly can often be quite special to many, because rather than going through a world 3 artifact to gain insights to other’s knowledge, we remain in world 2 and thus get it straight from the cognitive source, rather than an artifact. Plus, we can directly interact with the person through the use of questions, gestures, and other interactive means.

6 comments:

I like it as a taxonomy (not that anyone should care if I do or do not!).

How would it influence the design of a formal learning program to teach any of the following:

* business process improvement and business process reengineering

* contracting, sourcing, and outsourcing

* communication

* conflict management

* cost benefit analysis

* creating and using boards and advisors

* creating new tools

* decision-making

* ethics

* innovation/adaptation

* leadership

* negotiation

* nurturing/stewardship

* project management/program management

* relationship management

* researching

* risk analysis,

* management/security

* solutions sales

* teamwork

* turning around a bad situation.

Thanks Donald, this really fired some neurons! Popper's model contextualised a question I have been thinking about. How do you 'train' say 'revolutionary innovation?'

One of the key characteristics seems to be the ability to approach a subject or problem with knowledge from a radically different domain. I think of Einstein's methodology from his training in the patent office, or Faraday's Sandemanian beliefs affecting his work on magnetism. Or a yachtbuilder close to my previous hometown who built a carbonfibre racing catamaran partly inspired by the design of a bird's wing. It was two third's the weight of the nearest competitor and incredibly fast. The company's philosophy was to look to nature to solve design problems, as they believed the natural world (world 1)and not the theoretical world (world 3) provided all the solutions they needed.

So how then do you train someone to get to the correct analogous domain knowledge? Birds wing to boat or Religous belief to magnetism? How would you simulate that?

I am a great believer in the power of simulations to develop skill yet I do wonder if a boundary condition of sims is that they are built upon a systematic understanding of the world (you need a well defined world 3 understanding to build a sim if I understand Clark correctly). If the human capacity you wish to encourage rests on abilities that are difficult to systemise, perhaps because they happen in the adaptive unconscious then how do you train it? (and after all how on earth do you systemise these analagous inspirations between all 3 knowledge worlds)

I wonder if Popper's ideas are where the foundation for connectivism (first post constructivist learning philosophy as far as I can tell http://www.connectivism.ca/blog).

Here it seems attention will be drawn into the connection between things (as it is believed that the connection holds the knowledge, the space between worlds 1 and 2, because world 1 is an unknown until connected with world 2) And if this is what we come to believe, and I certainly think it's useful to apply connectivism to the capacity to innovate, then I wonder what strategies we'll construct for developing people?

Any suggestions?

Hope this all makes sense!

Gentlemen, I must admit that I am confused. I don't understand how Popper's model helps us improve performance.

I don't think this model has any direct effect on teaching one of the skills that Clark lists or improving performance as Jay suggests, on the other hand, I don’t believe there are many models, taxonomies, or theories that really do.

Even a lot of the books about learning don’t tell us how to improve skills or performance, even though they may string several models, ideas, and theories together to tell their story.

For example, Aldrich’s Simulations and the Future of Learning does not tell me how to build a simulation to teach any of the skills that he lists above and Rossett and Sheldon’s Beyond the Podium does not directly tell me how to improve performance. Does that mean these books have no use and that I wasted my time reading them? No. For they both make excellent background material that help to provide foundations and bridges for understanding our craft.

Even the books that get more into the 'how' normally only provide a piece of the puzzle, with a good example being Ruth Clark’s Graphics for learning. While being an excellent book on incorporating graphics into any learning package, it still does not provide the complete answer for building skills and improving performance. And this book is over 500 pages!

Perhaps one of Karl Popper’s best known theories was that scientific statements are those that can be put to the test and potentially proven wrong. It is not possible to prove that a hypothesis is true, but if the hypothesis is tested extensively and never proven false, then one accepts it as provisionally true. And if it turns out to be false in certain situations, then it can be modified or replaced.

Thus, I don’t believe that even Popper expected that his 'Three Worlds of Knowledge' model was the final answer for our understanding of knowledge, but rather a step forward.

So our hunt for the silver bullet performance model is still just that – a hunt.

One of the other interesting aspects of Popper's model is that knowledge is not only a noun, but it is also a verb. We see it as a noun in each of the three worlds -- the terms in world 1, residing within us in world 2, and in the artifacts we create in world 3. But as knowledge shifts from one world to the other, it becomes a verb, that is, it becomes a process rather than a product.

For example, the first hammer probably consisted of a rock (using world 2 knowledge in world 1). Then one day, someone got the bright idea of putting a handle on it to keep the fingers away from the striking area (of course the fingers on the other hand are still in the striking area, but that's another problem). In addition, the handle added leverage to it.

Thus, knowledge goes into building the first hammer, the knowledge becomes an artifact, and the knowledge is later recalled when someone uses the hammer. In addition, by observing and testing the world 3 product in world 1, we are able to use our knowledge to better the product or modify it for slightly different uses. For example, the first hammers had their handles lashed on, while most hammers built today have an eye in the head for the handle to slip through. In addition, there are now a variety of hammers for different or specialized uses.

If knowledge was simply a product (noun), we could easily transfer it to another person. You would show up for class, have a few products transferred to you, and then take them back to your workplace to use -- it becomes a matter of moving "contents" back and forth, such as transferring funds in a bank.

However, since knowledge is also a verb, it also implies a certain amount of context. Thus, we normally don't teach a "hammer", but rather the various contextual factors for using the "hammer:"

World 3 - The design of the artifact, rather it be an actual object, model, idea, or process normally communicates something about itself. Thus, it cues the learner on "known" factors that can be used for scaffolding.

World 2 - Cues the learner on what needs to be done or learned in order to perform.

World 1 - Facilitates the learning or doing.

World 3 and 1 Interaction - Tells where the learner is at in relationship to the actual performance itself.

I am going to suggest, albeit defensively, that Simulations and the Future of Learning talked all about a process and philosophy for creating content that does get straight to the issue of performance improvement via leadership. In fact, I get to avoid all of the "should it work?" conversations by having lots of independent research saying "it did and does work." Is SATFOL's and Virtual Leader's take on leadership totally comprehensive? No, but nothing ever will be totally comprehensive in the big skills. But it works really well, much better than scalable alternatives.

It is my belief that the same process can be used for any of the big skills.

Post a Comment